The Tragedy of Halbe: A Forgotten Battle of WWII's Final Days and the Battle of Berlin

Destroyed vehicles in the Spreewald forest

Introduction: World War II

The Battle of Halbe, fought in the final days of April 1945, remains one of the most brutal and least-known clashes of World War II’s endgame on the Eastern Front. As Soviet forces tightened their noose around Berlin, the beleaguered German Ninth Army found itself trapped in a shrinking pocket near the small village of Halbe, 30 miles southeast of the Nazi capital of Nazi Germany. Faced with the prospect of Soviet captivity, the Ninth Army’s only hope was a desperate breakout attempt against all odds. The ensuing struggle would consume thousands of lives, both military and civilian, in a maelstrom of fire, steel, and close-quarters fighting. This is the tragic story of the Halbe Pocket.

Strategic Context: Soviet Advance

By mid-April 1945, the Red Army had the German capital, Berlin, firmly in its sights. As part of their final offensive to capture the city and end the war in Europe, Soviet commanders sought to isolate and destroy the German Ninth Army. Positioned east of Berlin and defending the Oder River line, the Ninth Army, commanded by General Theodor Busse, represented a significant threat to the Soviet advance.

The Soviet Army, with its 2.5 million strong force, played a pivotal role in this final offensive, relentlessly pushing towards Berlin.

To eliminate this obstacle, Stalin ordered his two most formidable front commanders, Marshal Georgy Zhukov of the 1st Belorussian Front and Marshal Ivan Konev of the 1st Ukrainian Front, to encircle the Ninth Army and sever their lines of retreat. Zhukov would attack from the east, while Konev closed in from the south. Their ultimate objective was to trap the Germans in a pocket and prevent them from reinforcing Berlin’s defenses. This maneuver was part of a broader strategy to break through Army Group Centre and tighten the siege on Berlin.

Marshal Georgy Zhukov and Marshal Ivan Konev respectively

For General Busse and his men, estimated at around 200,000 soldiers along with thousands of refugees fleeing the Soviet advance, the prospect of being captured was unthinkable. The Soviets’ reputation for brutality towards prisoners, fueled by years of bitter fighting and Nazi atrocities on Soviet soil, meant that surrender was not an option. The Ninth Army’s only hope was to attempt to break out of the impending encirclement to the west and reach the relative safety of General Walther Wenck’s Twelfth Army.

However, any breakout attempt would have to punch through multiple layers of Soviet forces in the dense, swampy terrain of the Spreewald forest. This labyrinthine region of marshes, rivers, and thick woods presented a daunting challenge for mechanized warfare. The Germans would have to navigate narrow, easily congested roads and bridges, all while under constant Soviet fire. The stage was set for a desperate battle of attrition.

The Pocket Forms:

Under intense pressure from Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front from the east and Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front from the south, the Ninth Army’s defensive lines, manned by German forces, began to crumble. Soviet armour and infantry, backed by a formidable array of artillery and air support, tore through German positions along the Oder and Neisse Rivers. Despite determined resistance, Busse’s divisions could not hold back the Red Army tide.

Hitler and Busse at the last front-line meeting at the CI Army Corps, Harnekop Castle, March 3, 1945

By April 25th, Soviet pincers had closed around the Ninth Army, trapping them in a pocket roughly 15 miles wide and 8 miles deep in the Spreewald south of the village of Halbe. The Soviet 3rd and 28th Armies formed the northern edge of the pocket, while the 3rd Guards Tank Army and 13th Army sealed off the south. The Germans were now cut off from outside help and faced the daunting prospect of a fighting retreat through the Spreewald.

Soviet soldiers hoisted flags and banners to mark their victory, leaving graffiti as a testament to the liberation of the Reichstag.

Inside the “Halbe pocket,” conditions quickly deteriorated into a living nightmare. Cut off from resupply, the Germans soon began to run perilously low on food, ammunition, and medical supplies. Columns of vehicles, both military and civilian, jammed the narrow forest roads, presenting prime targets for marauding Soviet aircraft. Artillery fire rained down incessantly, shattering the woods and turning the roads into killing zones littered with burned-out wrecks and corpses of men and horses.

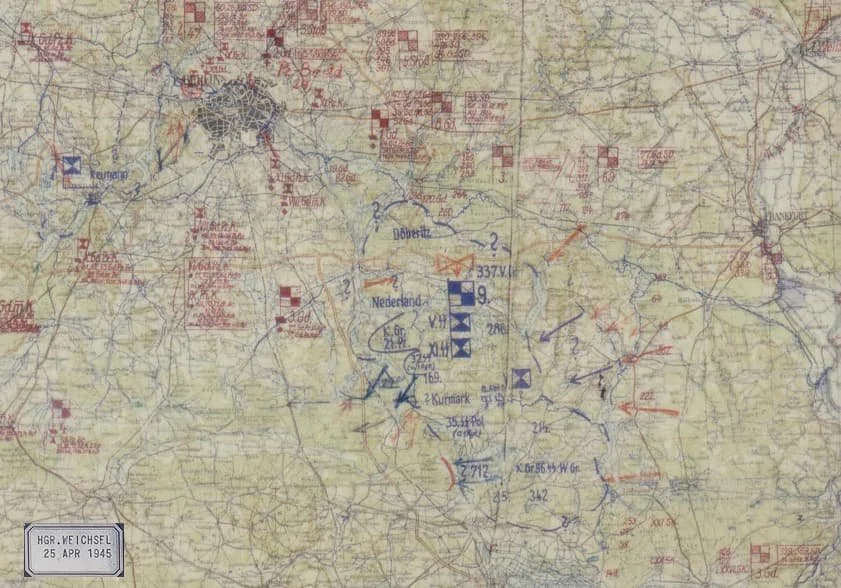

Map of the formation of the 9th Army pocket

As the pocket shrank under constant Soviet pressure, soldiers and refugees were forced into an ever tighter space, enduring intense privation and a mounting sense of claustrophobic doom. Makeshift field hospitals overflowed with wounded while the dead lay unburied. Food and water grew scarce. The hellish conditions eroded morale and unit cohesion, with some soldiers resorting to looting and abandoning their posts. The once-formidable Ninth Army was disintegrating.

Choosing Surrender: German Fears and Preferences in the War's Final Days

As the war in Europe drew to a close, German forces increasingly sought to surrender to the Western Allies rather than the Soviet Union. Several factors drove this preference. Firstly, there was a profound ideological enmity between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The Nazis viewed the Soviets as racially inferior and their communist ideology as a mortal threat to the German way of life.

Surrendering to the Soviets was thus seen as a deeply humiliating betrayal of core Nazi beliefs. Secondly, the Germans feared the prospect of brutal Soviet reprisals. They were acutely aware of the atrocities committed by Soviet forces as they advanced through Eastern Europe and anticipated harsh treatment and retribution as prisoners.

The Germans' own guilt compounded this fear; they had waged a pitiless war of annihilation against the USSR, seeking to destroy it as a political entity, murder and enslave its Slavic population, and colonize its territory. With the Soviets having suffered over 20 million deaths at German hands, the desire for vengeance was palpable. In contrast, the Germans had much less animosity towards the Western Allies, whom they had primarily fought to secure their rear before turning on the USSR.

Surrendering to the Americans or British was thus seen as a far preferable fate. This dynamic played out vividly in the Battle of Halbe, where desperate German forces fought to break out to the west and surrender to the Americans rather than fall into Soviet hands.

Halbe: The Eye of the Needle and Soviet Forces

Realizing that the pocket could not hold out for long, General Busse ordered his troops to mass west of Halbe to prepare for a breakout towards the spearheads of General Wenck’s Twelfth Army, which was advancing from the west. The small riverside village of Halbe, strategically located at a crossroads in the heart of the Spreewald, would be the focal point of the escape attempt. Troops soon began calling it “the eye of the needle” through which the entire Ninth Army would have to pass. The Army Group Vistula, under immense pressure, played a crucial role in the defensive preparations and strategies during this period.

Destroyed German vehicles

Starting on April 28th, the breakout began in earnest, spearheaded by the SS Panzer Division “Kurmark” and elements of the 502nd SS Heavy Tank Battalion. The Germans threw their remaining armour and veteran infantry units into the thrust, hoping to punch a corridor through the Soviet lines. However, the narrow confines of the forest roads and the density of Red Army soldiers meant that the battle rapidly devolved into a chaotic, brutal slugfest at close quarters.

Savage fighting erupted at strong points like the Halbe cemetery and railway embankment. At the cemetery, the struggle reached a crescendo of horror, with German troops using the stacked corpses of their own dead as makeshift breastworks against Soviet attacks. The armoured vehicles of both sides duelled at point-blank range amidst the tombstones while infantry grappled in hand-to-hand combat among the crypts.

Soviet war map showing the battle lines of the 9th Army encirclement.

Nearby, the elevated railway embankment became a scene of equal carnage. Soviet troops entrenched along its length poured fire into the advancing Germans, turning the railbed into a charnel house. Burned-out tanks and shattered bodies choked the narrow confines. The fighting devolved into a series of ruthless small-unit actions, with squads and platoons clashing in a maelstrom of bullets, grenades, and flamethrowers.

As the battle raged, thousands of terrified refugees found themselves caught in the crossfire. Desperate columns of civilians, their meagre possessions piled on carts and wagons, clogged the roads. Many were killed by stray shells or machine-gun fire as they tried to flee westward. Others fell victim to vengeful Soviet troops, who viewed them as complicit in German crimes. The fate of the refugees added an especially tragic dimension to the unfolding disaster.

Breakout and Aftermath of German Forces

After days of brutal fighting that gutted the Ninth Army, a group of about 25,000 haggard German troops finally managed to break through the Soviet gauntlet and reach the temporary safety of Wenck’s lines. The survivors emerged from the Spreewald battered, bloodied, and traumatized by their ordeal. Many had lost everything—their units, their comrades, their families. The physical and psychological scars would linger long after the guns fell silent.

The Soviet Union commemorated the battle by honouring the Hero of the Soviet Union recipients and awarding medals to Soviet personnel for their actions during the Battle of Berlin.

Twisted metal still visible from the aftermath of the Halbe Pocket breakout attempt.

But the Germans’ escape had come at a staggering cost. In their wake, they left scenes of unimaginable devastation and carnage. Corpses carpeted the forest floor, piled in grotesque tangles where they had fallen. Burned-out hulks of tanks, trucks, and wagons littered the roadsides for miles, a testament to the ferocity of the fighting. The pungent stench of death hung over the battleground.

The human toll of the Halbe pocket was appalling. Scholars estimate that at least 40,000 German soldiers perished in the breakout attempt, with another 20,000 wounded. Between 20,000 and 30,000 hapless refugees were also killed, cut down in the crossfire or deliberately targeted by Soviet troops. The Red Army claimed to have taken 60,000 prisoners, many of whom would endure years of forced labour in Soviet gulags.

The Battle of Halbe, while small in scale compared to the titanic clashes of the Eastern Front’s earlier years, nonetheless epitomized the relentless brutality and human tragedy of the war’s endgame. It laid bare the utter collapse of the once-vaunted Wehrmacht, ground down by years of attrition and material disadvantage. It highlighted the pitiless calculus of total war, in which entire armies and civilian populations could be sacrificed in the pursuit of victory. And it underscored the Third Reich’s dismal moral bankruptcy, as Nazi leaders consigned thousands to senseless death in a battle already lost.

Halbe also represented a microcosm of the “total war” that had engulfed the Eastern Front, erasing distinctions between soldiers and civilians. Alongside the doomed German military units fought the Volkssturm, a ragtag people’s militia of old men and teenagers pressed into service in the regime’s final days. Refugees fleeing the Soviets found themselves thrust onto the front lines, where they perished alongside the troops meant to protect them. In the Spreewald inferno, all became targets.

German POWs

The fall of Berlin, marked by Adolf Hitler's death by suicide in the bunker beneath the Old Chancellery building, signalled the end of the Third Reich. The subsequent Battle of Berlin led to the city's fall to Soviet forces, resulting in significant casualties and the razing of the city. The Soviet War Memorial at Tiergarten commemorates this pivotal event and serves as a pilgrimage site for Red Army veterans and their families.

Remembering Halbe:

Despite the intensity of the fighting and the scale of the tragedy, the Battle of Halbe has long remained a historical footnote, overshadowed by the high-profile fall of Berlin unfolding simultaneously just 30 miles to the north. The chaotic nature of the final days on the Eastern Front, combined with the thorough Soviet conquest of eastern Germany, meant that many records of the battle were lost or deliberately suppressed.

For decades after the war, East Germany’s communist authorities actively discouraged research into the Halbe pocket and other desperate battles fought on what became their territory. The story of Halbe complicated the triumphalist postwar Soviet narrative, which emphasized the Red Army’s heroic liberation of Germany from Nazism. Acknowledging the scope of civilian suffering and the brutal realities of the Spreewald fighting did not align with the official historiography.

German Army soldiers bury remains in Halbe cemetery, 2013

The Soviet War Memorial in Tiergarten, Berlin, constructed using materials from destroyed Nazi office buildings, serves as a significant reminder of the Red Army's role and the sacrifices made, including the surrounding cemetery for fallen Red Army soldiers and the annual VE-Day commemorations.

As a result, the Battle of Halbe faded into relative obscurity, mourned by veterans and families of the fallen but little known to the broader public. Only after German reunification in 1990 did historians begin to document and chronicle the battle extensively. Halbe has since become a subject of intensive research and sombre commemoration.

Today, the memory of Halbe is preserved by a melancholy war cemetery in the nearby forest, where over 22,000 German soldiers and civilians are interred in mass graves. A small museum in the village also endeavours to tell the story of the doomed breakout attempt. In recent years, several powerful and harrowing books have brought the battle’s history to a wider audience, including Tony Le Tissier’s “Slaughter at Halbe” and Anne-Katrin Müller’s “The Battle of Halbe: The Destruction of the Ninth Army.”

Halbe War Grave Cemetery

Beyond its memorials and chroniclers, however, Halbe endures as a sobering reminder of the human suffering unleashed by war at its most unsparing. On this small, blood-soaked battlefield, where shell-shocked conscripts fought alongside hardened veterans, where terrified families fleeing an implacable foe fell beside the fanatical remnants of the Waffen-SS, we glimpse the Eastern Front distilled to its brutal essence. It is a harrowing picture of depravity, desperation, and ordinary people caught in the meat grinder of total war. The broader context of the war's end also saw German troops seeking to surrender to the Western Allies, fearing the fate of Soviet captivity, and the Western Allies' subsequent withdrawal to agreed-upon boundaries after Germany's unconditional surrender.

Conclusion:

The Battle of Halbe, while a small chapter in the vast saga of World War II, nonetheless looms large in the bloody drama that played out in central Europe during the spring of 1945. It offers a microcosmic glimpse into the agonizing final days on the Eastern Front, with all their attendant chaos, horror, and moral ambiguity. It reveals the human face of the German army's collapse—from the travails of General Busse's doomed divisions to the plight of the terrified refugees swept up in their wake.

Halbe deserves to be remembered not only as a testament to the immense suffering and sacrifice of those caught in its maelstrom but also as a cautionary tale about the profound costs of war fought to the bitter end. In an age when "total war" became an all-consuming reality, erasing distinctions between soldier and civilian, front line and home front, Halbe reminds us of the price paid by all—the vanquished no less than the victors—when nations clash without restraint or mercy.

As we reflect on this tragic battle 75 years later, let us honour the memory of those who struggled, suffered, and perished in the Spreewald cauldron. Germans and Soviets, men and women, young and old—all were consumed in the inferno unleashed by a brutal, rapacious war and the totalitarian ideologies that fueled it. May their sacrifice not be forgotten, and may it stand as a sombre warning to future generations of the horrors lurking in the heart of total war.

The article was written by Matthew Menneke.

Matt is the founder and guide of 'On the Front Tours', offering military history tours in Berlin. Born in Melbourne, Australia, Matt's passion for history led him to serve in the Australian Army Reserve for eight years. With a degree in International Politics and a successful sales career, he discovered his love for guiding while working as a tour guide in Australia. Since moving to Berlin in 2015, Matt has combined his enthusiasm for history and guiding by creating immersive tours that bring the past to life for his guests.