Nazi Germany Collapse: The Battle of Halbe and the True Horror of War's End

By Matthew Menneke

In the dense pine forests southeast of Berlin, 80 years ago this spring, one of World War II’s most desperate and brutal battles unfolded in near-complete obscurity. While the world’s attention focused on Adolf Hitler’s leadership during the final days in Berlin's bunker and the fall of the German capital, nearly 200,000 German soldiers and civilians fought a savage running battle through the Spree Forest, desperately trying to escape Soviet encirclement and reach American lines to the west.

The Battle of Halbe, fought from April 24 to May 1, 1945, represents everything horrific about the war’s final days on the Eastern Front. It’s a story of impossible choices, blurred lines between soldier and civilian, and the lengths people will go to avoid a fate they consider worse than death. Yet despite its scale and significance, this battle remains largely forgotten, overshadowed by the more famous siege of Berlin and relegated to the margins of popular World War II history.

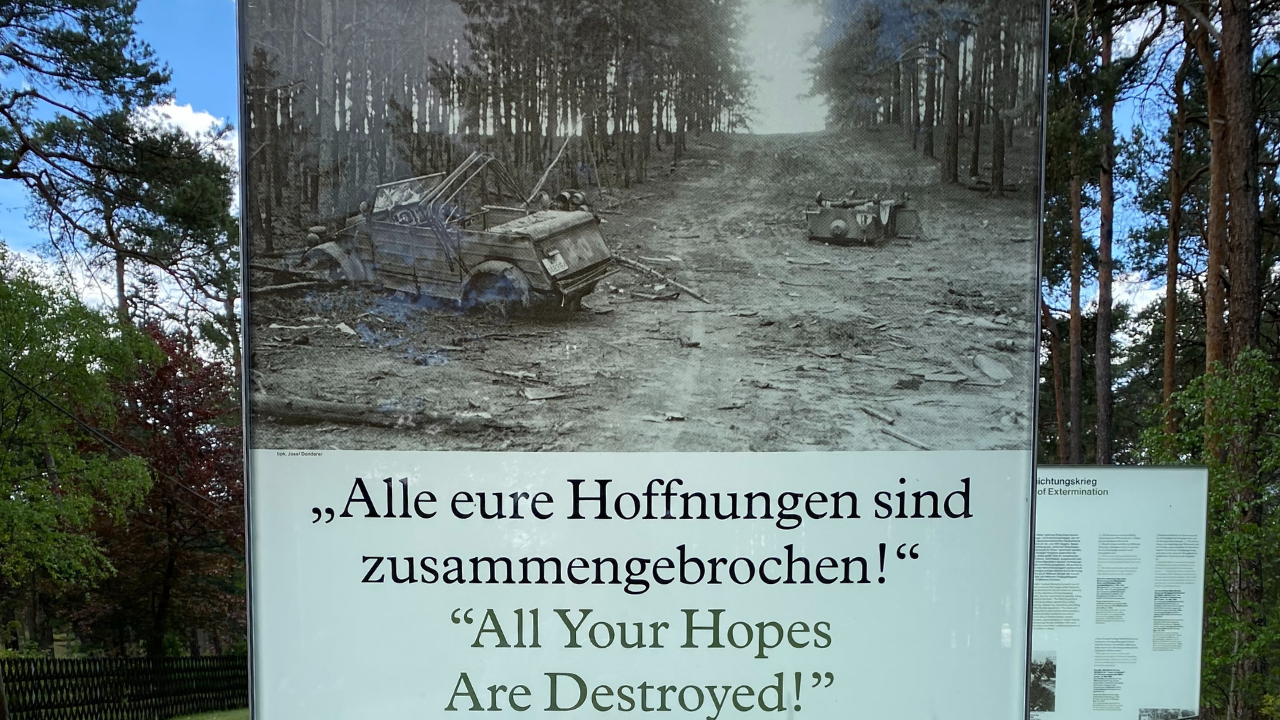

Translation: Street in the Halbe Pocket, May 1945

The Forgotten Battlefield of the Battle of Halbe That Still Echoes Today

Walking through the forests around Halbe today, you encounter an eerie silence that belies the hell that unfolded here eight decades ago. The pine trees stand tall and peaceful, but beneath the forest floor lie the remnants of one of the war’s most desperate battles. Unlike the famous World War I battlefields of France, where the earth annually yields its buried artefacts in what farmers call the “iron harvest,” Halbe’s relics remain largely undisturbed on the surface.

Shrapnel still litters the forest floor—destroyed vehicles rust where they fell. Personal equipment, weapons, and even pieces of Enigma machines can still be found by those who know where to look. Among all the discoveries, the regular surfacing of human remains is the most haunting. The German War Graves Commission conducted major burials in 2020 and 2022, each time interring roughly 80 bodies discovered since their previous efforts. The Halbe Forest Cemetery now contains about 24,000 German burials, making it the largest World War II cemetery in Germany, with about 10,000 graves marked simply as “unknown”. Many of these are unidentified soldiers killed during the battle, reflecting the tragic scale of casualties and the difficulty in identifying all the fallen.

This ongoing discovery of the dead serves as a stark reminder that we may never know the true scale of what happened here. Conservative estimates suggest 60,000 people were killed or wounded in the battle, including 30,000 dead. But nobody knows how many civilians died – the number could have reached 10,000.

Halbe War Graves Cemetery

The Eastern Front: The War’s Most Brutal Theatre

The Eastern Front stands as the most savage and colossal theatre of World War II, where the fate of Europe was decided in a clash of titanic armies and ideologies. Here, Adolf Hitler’s German army launched its infamous invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941—Operation Barbarossa—unleashing a conflict that would dwarf all others in scale and brutality. Stretching from the icy Baltic Sea to the sun-baked shores of the Black Sea and from the Polish border deep into the heart of the Soviet Union, this front became a vast killing ground.

Initial rapid advances marked the German invasion, but the Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin, marshalled its immense resources and manpower to resist, turning the tide in a series of epic battles. The Eastern Front witnessed the siege of cities like Leningrad, the industrial inferno of Stalingrad, and the armoured clash at Kursk—the largest tank battle in history. It was not just a military struggle but a war of annihilation, with both sides committing atrocities on a scale rarely seen before or since. Millions of soldiers and civilians perished, entire towns were erased, and the relentless advance and retreat of ground forces scarred the landscape itself.

For four years, the German army and the Soviet Union fought a war of attrition, with the Eastern Front consuming men and materiel at a staggering rate. The brutality of this theatre set the stage for the desperate final battles of 1945, as the Red Army closed in on Berlin and the remnants of the German armed forces made their last stand.

German infantry advancing on foot. Unknown location, Russia.

When the German Ninth Army Became a "Caterpillar"

The battle began as the inevitable result of the Red Army’s massive offensive toward Berlin. On April 16, 1945, over 3 million Soviet soldiers launched a three-front attack across the Oder-Neisse line. The German Ninth Army, under General Theodor Busse, had been defending the Seelow Heights against Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, but was outflanked by Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front attacking from the south. The Soviet advance threatened the Ninth Army's front lines, and soon soviet pincers closed around the German forces, trapping them.

By April 21, Soviet forces had broken through German lines and begun the encirclement that would trap approximately 80,000 German troops in the Spree Forest region. Many German troops, along with an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 civilians – not just local residents of towns like Halbe, but German refugees fleeing westward from East Prussia and Silesia as the Red Army advanced – were caught in the pocket.

General Busse described his breakout plan to General Walther Wenck of the Twelfth Army using a vivid metaphor: the Ninth Army would push west “like a caterpillar.” The Tiger II heavy tanks of the 102nd SS Heavy Panzer Battalion would lead this caterpillar’s head, while the rear guard would fight just as desperately to disengage from pursuing Soviet forces. Fleeing German forces, mixed with civilians, attempted to escape the encirclement in what became a 60-kilometre running battle through hell.

Destroyed German vehicles, Halbe, 1945

The Soviet Advance: The Red Army Closes In

By the spring of 1945, the tide of war had turned decisively in favour of the Soviet Union. The Red Army, hardened by years of brutal combat and driven by the desire to end Nazi Germany’s reign of terror, launched a series of relentless offensives that would bring the war in Europe to its bloody conclusion. Under the command of Marshal Georgy Zhukov and Marshal Ivan Konev, the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts spearheaded the Soviet advance, coordinating massive assaults that overwhelmed the exhausted German army.

The soviet army’s strength was overwhelming: millions of soldiers, thousands of tanks, and a seemingly endless barrage of artillery fire. As the Red Army surged westward, the German army—once the most formidable fighting force in Europe—was now battered, depleted, and demoralised. Nazi Germany’s hopes of holding back the Soviet advance evaporated as the Red Army’s pincers closed around Berlin, cutting off escape routes and encircling entire German formations.

The final Soviet offensives were marked by speed and ferocity, with soviet troops determined to crush any remaining resistance. The German army, unable to withstand the onslaught, was forced into a chaotic retreat, leaving behind countless dead and wounded. For many German soldiers, the prospect of falling into Soviet hands was terrifying, fueling desperate attempts to break out and surrender to the Western Allies instead. The Red Army’s relentless push not only sealed the fate of Berlin but also ensured that the Eastern Front would be remembered as the crucible in which Nazi Germany was finally destroyed.

Soviet troops advance into Berlin's urban suburbs.

The Impossible Choice: Fight or Surrender

Understanding why the Battle of Halbe happened at all requires grasping the impossible situation facing German soldiers and civilians in April 1945. For Wehrmacht personnel, surrender to the Soviets meant almost certain death or years in the gulag system. The statistics were stark: Germany lost 3 million soldiers during the war but lost an equivalent number–nearly 2 million more–in Soviet captivity between 1945 and 1954, when the last German prisoner was finally released.

For SS personnel, the choice was even starker – Soviet forces rarely took SS prisoners alive. For civilians, particularly women, surrender meant facing the systematic rape and brutalisation that had characterised the Red Army's advance through Eastern Europe. As one historian noted, "There are no civilians, there are no non-combatants really at this stage, particularly in the minds of the Soviets, as they're pushing ever so closer to Berlin."

This created a powerful motivation that transcended military discipline or Nazi ideology. General Busse motivated his troops not with promises of victory, but with hope: "Let's go west. Let's live. Let's get across the Elbe. Let's surrender to the Americans." The plan was to break through to Wenck's Twelfth Army and then continue west to American lines, where they expected more humane treatment.

The Soviets understood this psychology perfectly. Their propaganda leaflets dropped over German positions read: "All your hopes are destroyed." But for many Germans, any hope, however slim, was better than the certainty of Soviet captivity.

Information panel located at the Halbe War Graves

Artillery Rain and Tree-Burst Hell

The tactical reality of the Battle of Halbe was dominated by one factor above all others: Soviet artillery. Facing the German breakout were approximately 280,000 Soviet troops with 7,400 guns and mortars, 280 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 1,500 aircraft. Among these forces, the 1st Guards Breakthrough Artillery Division played a crucial role in smashing through German defences and using concentrated firepower to open gaps for Soviet advances. The Soviets had learnt to use the forest terrain to their advantage, deliberately timing their artillery shells to explode at tree-top height.

This technique, which had previously devastated American forces in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, created a deadly rain of wooden splinters that supplemented the metal fragments from the shells themselves. The sandy soil of the pine forests made digging foxholes impossible, leaving German troops with virtually no protection from this aerial bombardment.

Soviet aircraft relentlessly targeted German positions and supply lines, further isolating the encircled forces and hampering any organised resistance.

As one witness described it: “It’s the artillery which is bringing raining effectively death down from above. And there’s nothing you can do against artillery. It just comes. Doesn’t matter how skilled you are as a soldier… it just comes down to effectively dumb luck that it doesn’t hit you.”

The German forces found their armour largely useless in this environment. Tanks were vulnerable to destruction on the roads and struggled to gain proper traction on the sandy forest soil. The Soviets countered with dug-in Soviet tanks, establishing fortified positions that were difficult to dislodge and provided strong defensive fire against German breakout attempts. The dense forest terrain reduced visibility to mere metres, creating constant danger of ambush for both sides. Smoke from burning sections of forest, set alight by shell fire, provided some concealment from Soviet aerial reconnaissance but also disoriented German troops who lacked compasses and couldn’t see the sun for navigation. Both sides operated with few or no maps, which increased the chaos and confusion during the battle.

Destroyed vehicles along a forest track

The Civilian Tragedy Hidden in Plain Sight

Perhaps the most overlooked aspect of the Battle of Halbe is the civilian tragedy that unfolded alongside the military action. Thousands of non-combatants were caught in the battle zone, including local residents and refugees who had been fleeing westward for months.

In the town of Halbe itself, some civilians took pity on very young soldiers – the so-called “Kindersoldaten” or child soldiers – and allowed them to change out of their uniforms into civilian clothes. But the line between civilian and combatant had long since blurred. The Volkssturm, Germany’s civilian militia, had been pressed into service with basic weapons, and by this stage of the war, anyone capable of holding a Panzerfaust might be handed one and told to face a Soviet tank.

The civilian death toll remains unknown, but estimates suggest it could have reached 10,000. These deaths occurred not just from the fighting itself, but from the systematic targeting of civilian columns by the Soviet attack, as Soviet forces deliberately aimed their artillery and bombardments at specific targets, including groups of fleeing civilians. When American and Soviet forces linked up at the Elbe River, the famous footage of soldiers shaking hands over the bridge was actually staged. The real meeting point, just days earlier, was deemed unsuitable for filming because it was “peppered on the Soviet side of the river with all dead civilians that the Soviet artillery had been targeting”.

Spree forest track today

The Halbe Forest Cemetery: Memory Amid the Pines

Nestled among the tall, whispering pines, the Halbe Forest Cemetery stands as a solemn testament to the sacrifice and suffering of the Battle of Halbe. Here, in the heart of the forest where so many fell, thousands of German soldiers lie buried—many in mass graves, their identities lost to the chaos of war. Simple wooden crosses and understated markers bear silent witness to the final days of World War II, when the forests around Halbe became a killing ground for soldiers and civilians alike.

The cemetery, maintained by the German War Graves Commission, is more than just a burial site; it is a place of remembrance and reflection. Each year, families and visitors come to pay their respects, laying flowers and pausing in the quiet shade to honour those who never returned home. The Halbe Forest Cemetery is now the largest World War II cemetery in Germany, a stark reminder of the scale of loss suffered in the battle’s final, desperate days.

Amid the tranquillity of the pines, the cemetery serves as a powerful reminder of the devastating consequences of war. It stands not only as a memorial to the German soldiers who fought and died in the Battle of Halbe, but also as a call for peace and reconciliation—a place where the lessons of the past echo quietly through the forest, urging future generations never to forget the true cost of conflict.

Hale Forest Cemetery

Why Halbe Remains Forgotten

Despite its scale and significance, the Battle of Halbe remains largely unknown, even to many Germans living in the region. Several factors contribute to this historical amnesia, especially in the context of post-war Germany, where the memory of such battles has often been overshadowed or deliberately neglected.

First, Western audiences naturally focus on battles involving their own forces, such as those in Normandy, Market Garden, and the Rhine crossing, rather than the purely German-Soviet confrontations on the Eastern Front. The Eastern Front’s complexity, involving multiple nationalities and ideologies, makes it harder for Western audiences to understand and relate to.

Second, the battle gets lost in the broader narrative of the Battle of Berlin. When people think of Berlin’s fall, they focus on the city itself – Hitler’s bunker, the Reichstag, the famous Soviet flag photograph. But the Battle of Berlin actually began 90 kilometres outside the city, at places like the Seelow Heights and Halbe. The Seelow Heights alone involved 1 million men, including 768,000 infantry, four times larger than the entire Normandy operation.

Third, post-war sensitivities have kept the story buried. The Soviets didn’t want to discuss what many viewed as war crimes against civilians. The Germans, as the losing side, couldn’t bring attention to their own victimisation. And in modern Germany, there’s hypersensitivity to anything that might be seen as sympathizing with Nazi causes, even when discussing genuine human suffering.

Ultimately, the battle challenges comfortable narratives about the end of World War II. It reveals the savage reality of the Eastern Front, where both sides committed atrocities and the line between liberation and conquest became hopelessly blurred.

The line of advance for German soldiers into the town of Halbe today.

The Scale That Defies Comprehension

To understand why Halbe has been overlooked, it’s crucial to grasp the almost incomprehensible scale of Eastern Front operations. The Battle of Berlin involved over 3 million Soviet soldiers – a number that dwarfs most Western Front operations. These massive battles were coordinated by large army group formations, with German Army Group Centre and Army Group Vistula playing key roles in the final defensive efforts. The Seelow Heights, just one component of three Soviet fronts, was four times larger than the entire Normandy campaign, which landed 250,000 Allied troops. The scale and effectiveness of Soviet force dispositions during these operations were decisive in encircling and overwhelming German forces.

These numbers become even more staggering when considering Soviet record-keeping practices. The Soviets only officially recorded deaths of Communist Party members, leading to massive underreporting of casualties. Before the Battle of Berlin, party membership applications swelled as soldiers wanted their families notified if they were killed. Polish casualties – 80,000 Poles fought at the Seelow Heights – were never officially recorded at all.

The German War Graves Commission has recovered 1 million German war dead from Eastern Europe since 1945, recently completing a “Million for a Million” campaign to raise funds for repatriation. But there’s no equivalent Russian effort to recover Soviet remains, and Eastern European countries often bury their citizens who fought for Germany quickly and quietly, viewing their service as a source of shame.

Soviet artillery firing the opening barrage during the Battle for the Seelow Heights, April 1945

The Human Story Behind the Statistics

At its core, the Battle of Halbe reveals warfare as an inherently human story, not just a clash of machines and strategies. The soldiers on both sides had similar characteristics, similar hopes and fears. In any other circumstances, they might have been friends. But the cauldron of war, particularly the ideological war of the Eastern Front, brought out humanity’s ugliest side.

For the average German soldier at Halbe, part of the encircled army facing impossible odds, the motivation to keep fighting wasn’t ideological fanaticism but something more basic: “For the average man on the ground, it’s this sense of, well, I’m here now. I can’t do anything about my situation. I can’t run away, I can’t do anything about that. And then there’s a man next to me, who’s in the same boat that I am. So I gotta fight.”

This sense of duty to the soldier beside you, combined with the very real threat of execution by German military police for desertion, meant that for many, there simply was no choice. Roving court martials publicly executed soldiers and civilians for fleeing the battlefield, hanging them from street lamps with placards calling them cowards and traitors.

The Bundeswehr conducted a burial ceremony for bodies recovered after German unification.

Lessons from Hell's Cauldron

The Battle of Halbe offers several crucial insights into the nature of warfare and human behaviour under extreme stress. Author Eberhard Baumgart, who collected eyewitness accounts from the battle, identified key factors that determined who survived and who didn’t.

Success in the breakout depended largely on belonging to units where military authority and discipline remained intact: “To put it bluntly, the answer is those who belonged to regiments, battalions and companies where authority had remained intact and where there was a direct link between order and obedience. That’s where the combative spirit triumphed.” The discipline and organisation maintained by German units played a crucial role in preserving order and enabling coordinated attempts at breakout, even as chaos mounted.

The resolve displayed by German forces was rooted in their firsthand experience of Red Army cruelty: “The resolve displayed by the Ninth Army was also rooted in their firsthand experience of the Red Army’s cruelty. It was this certainty and the relentless barbarity shown in the ensuing slaughter which led to the scream ‘Run for your lives!’ reverberating through the ranks.” The Ninth Army's situation during the encirclement was especially dire, with their desperate actions and determination standing out as a testament to their resolve under extreme pressure.

But this desperation also led to the collapse of military effectiveness. Demoralised troops would retreat at the first obstacle, waiting for others to take casualties while hoping to tag along with successful breakthrough attempts. Those who did attempt the breakout faced continuous battles over 60 kilometres: “Those who embarked on the breakthrough ended up having to tackle one battle after another. The minute one obstruction had been surmounted, there was another one ahead of them, and then another. That happened day after day, for sixty long kilometres.”

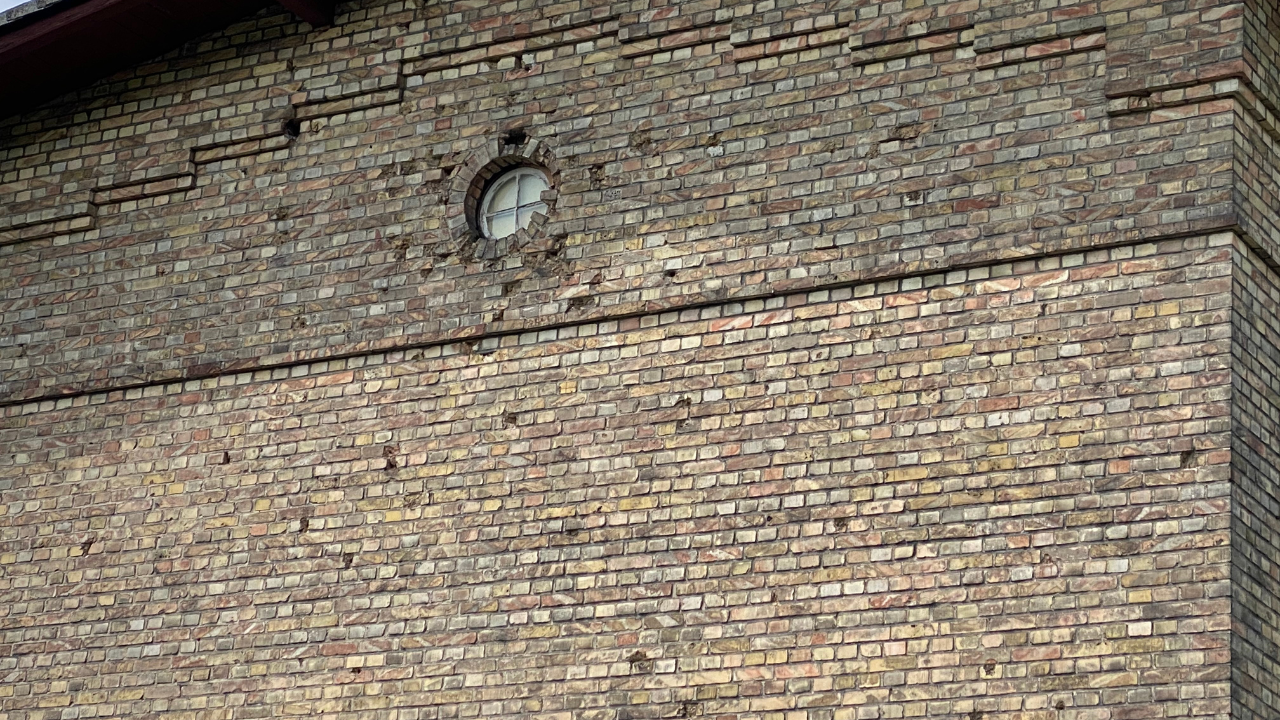

Battle scares still visible today on a residential property near the Halbe train station

The Aftermath: Success and Tragedy

Despite the horrific casualties, the Battle of Halbe achieved its primary objective for many participants. Approximately 30,000 German soldiers – just over one-third of those originally encircled – successfully reached the Twelfth Army’s lines. Combined with civilian refugees, these survivors then continued their westward retreat, eventually crossing the Elbe River at Tangermünde between May 4-7, 1945, to surrender to elements of the U.S. 102nd Infantry Division. In the final stages of the battle, Soviet forces plugged the last escape routes, sealing the fate of the encircled Germans and preventing further breakouts.

But the cost was enormous. The remaining 50,000 soldiers were killed or captured. The Red Army claimed to have taken tens of thousands of prisoners and reported significant victories in the destruction of German forces. Soviet casualties were also heavy, with thousands of Red Army soldiers buried at the Sowjetische Ehrenfriedhof cemetery near Baruth. The civilian toll may never be fully known, but it represents one of the war’s final tragedies – non-combatants caught between armies in the conflict’s dying days.

German POW’s April 1945

Conclusion: Remembering the Forgotten

The Battle of Halbe deserves to be remembered not as a footnote to the Battle of Berlin but as a crucial chapter in understanding the end of World War II and the human cost of ideological warfare. It reveals the desperate lengths people will go to when faced with impossible choices, the breakdown of military and social order in war’s final stages, and the blurred lines between combatant and civilian that characterised the Eastern Front and the brutal conflicts that swept across central Europe.

Today, as we approach the 80th anniversary of these events, the forests around Halbe remain a powerful memorial to those who died there. The silence that now pervades these woods stands in stark contrast to the hell that unfolded here in April 1945. Every year, more remains surface, reminding us that the full story of this battle – and the full accounting of its human cost – may never be complete.

The Battle of Halbe forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about warfare, ideology, and human nature. It challenges simple narratives of good versus evil, liberation versus conquest. Most importantly, it reminds us that behind every statistic, every casualty figure, every strategic decision, lie individual human stories of courage, desperation, and tragedy.

In remembering Halbe, we honour not just the soldiers who fought there but all those caught in war’s machinery – the civilians who had no choice but to flee, the young soldiers pressed into service, and the families torn apart by ideology and violence. Their stories deserve to be told, their sacrifices remembered, and their humanity acknowledged, even 80 years after the guns fell silent in the forests of Brandenburg.

This article was written by Matthew Menneke.

Matt is the founder and guide of 'On the Front Tours', offering military history tours in Berlin. Born in Melbourne, Australia, Matt's passion for history led him to serve in the Australian Army Reserve for eight years. With a degree in International Politics and a successful sales career, he discovered his love for guiding while working as a tour guide in Australia. Since moving to Berlin in 2015, Matt has combined his enthusiasm for history and guiding by creating immersive tours that bring the past to life for his guests.