Nazi Germany Collapse: The Battle of Halbe and the True Horror of War's End

In April 1945, as Berlin fell, 200,000 German soldiers and civilians fought to escape a Soviet trap in Halbe. A brutal, forgotten battle where survival meant impossible choices.

By Matthew Menneke

In the dense pine forests southeast of Berlin, 80 years ago this spring, one of World War II’s most desperate and brutal battles unfolded in near-complete obscurity. While the world’s attention focused on Adolf Hitler’s leadership during the final days in Berlin's bunker and the fall of the German capital, nearly 200,000 German soldiers and civilians fought a savage running battle through the Spree Forest, desperately trying to escape Soviet encirclement and reach American lines to the west.

The Battle of Halbe, fought from April 24 to May 1, 1945, represents everything horrific about the war’s final days on the Eastern Front. It’s a story of impossible choices, blurred lines between soldier and civilian, and the lengths people will go to avoid a fate they consider worse than death. Yet despite its scale and significance, this battle remains largely forgotten, overshadowed by the more famous siege of Berlin and relegated to the margins of popular World War II history.

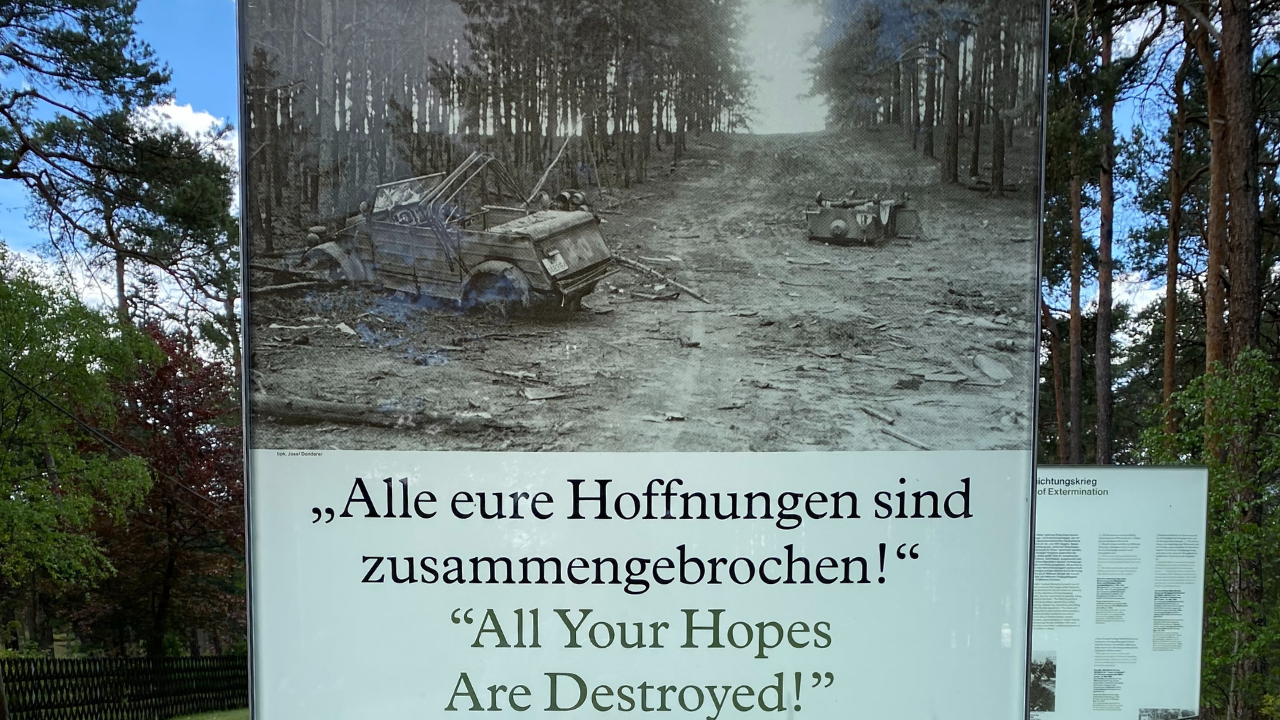

Translation: Street in the Halbe Pocket, May 1945

The Forgotten Battlefield of the Battle of Halbe That Still Echoes Today

Walking through the forests around Halbe today, you encounter an eerie silence that belies the hell that unfolded here eight decades ago. The pine trees stand tall and peaceful, but beneath the forest floor lie the remnants of one of the war’s most desperate battles. Unlike the famous World War I battlefields of France, where the earth annually yields its buried artefacts in what farmers call the “iron harvest,” Halbe’s relics remain largely undisturbed on the surface.

Shrapnel still litters the forest floor—destroyed vehicles rust where they fell. Personal equipment, weapons, and even pieces of Enigma machines can still be found by those who know where to look. Among all the discoveries, the regular surfacing of human remains is the most haunting. The German War Graves Commission conducted major burials in 2020 and 2022, each time interring roughly 80 bodies discovered since their previous efforts. The Halbe Forest Cemetery now contains about 24,000 German burials, making it the largest World War II cemetery in Germany, with about 10,000 graves marked simply as “unknown”. Many of these are unidentified soldiers killed during the battle, reflecting the tragic scale of casualties and the difficulty in identifying all the fallen.

This ongoing discovery of the dead serves as a stark reminder that we may never know the true scale of what happened here. Conservative estimates suggest 60,000 people were killed or wounded in the battle, including 30,000 dead. But nobody knows how many civilians died – the number could have reached 10,000.

Halbe War Graves Cemetery

The Eastern Front: The War’s Most Brutal Theatre

The Eastern Front stands as the most savage and colossal theatre of World War II, where the fate of Europe was decided in a clash of titanic armies and ideologies. Here, Adolf Hitler’s German army launched its infamous invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941—Operation Barbarossa—unleashing a conflict that would dwarf all others in scale and brutality. Stretching from the icy Baltic Sea to the sun-baked shores of the Black Sea and from the Polish border deep into the heart of the Soviet Union, this front became a vast killing ground.

Initial rapid advances marked the German invasion, but the Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin, marshalled its immense resources and manpower to resist, turning the tide in a series of epic battles. The Eastern Front witnessed the siege of cities like Leningrad, the industrial inferno of Stalingrad, and the armoured clash at Kursk—the largest tank battle in history. It was not just a military struggle but a war of annihilation, with both sides committing atrocities on a scale rarely seen before or since. Millions of soldiers and civilians perished, entire towns were erased, and the relentless advance and retreat of ground forces scarred the landscape itself.

For four years, the German army and the Soviet Union fought a war of attrition, with the Eastern Front consuming men and materiel at a staggering rate. The brutality of this theatre set the stage for the desperate final battles of 1945, as the Red Army closed in on Berlin and the remnants of the German armed forces made their last stand.

German infantry advancing on foot. Unknown location, Russia.

When the German Ninth Army Became a "Caterpillar"

The battle began as the inevitable result of the Red Army’s massive offensive toward Berlin. On April 16, 1945, over 3 million Soviet soldiers launched a three-front attack across the Oder-Neisse line. The German Ninth Army, under General Theodor Busse, had been defending the Seelow Heights against Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, but was outflanked by Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front attacking from the south. The Soviet advance threatened the Ninth Army's front lines, and soon soviet pincers closed around the German forces, trapping them.

By April 21, Soviet forces had broken through German lines and begun the encirclement that would trap approximately 80,000 German troops in the Spree Forest region. Many German troops, along with an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 civilians – not just local residents of towns like Halbe, but German refugees fleeing westward from East Prussia and Silesia as the Red Army advanced – were caught in the pocket.

General Busse described his breakout plan to General Walther Wenck of the Twelfth Army using a vivid metaphor: the Ninth Army would push west “like a caterpillar.” The Tiger II heavy tanks of the 102nd SS Heavy Panzer Battalion would lead this caterpillar’s head, while the rear guard would fight just as desperately to disengage from pursuing Soviet forces. Fleeing German forces, mixed with civilians, attempted to escape the encirclement in what became a 60-kilometre running battle through hell.

Destroyed German vehicles, Halbe, 1945

The Soviet Advance: The Red Army Closes In

By the spring of 1945, the tide of war had turned decisively in favour of the Soviet Union. The Red Army, hardened by years of brutal combat and driven by the desire to end Nazi Germany’s reign of terror, launched a series of relentless offensives that would bring the war in Europe to its bloody conclusion. Under the command of Marshal Georgy Zhukov and Marshal Ivan Konev, the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts spearheaded the Soviet advance, coordinating massive assaults that overwhelmed the exhausted German army.

The soviet army’s strength was overwhelming: millions of soldiers, thousands of tanks, and a seemingly endless barrage of artillery fire. As the Red Army surged westward, the German army—once the most formidable fighting force in Europe—was now battered, depleted, and demoralised. Nazi Germany’s hopes of holding back the Soviet advance evaporated as the Red Army’s pincers closed around Berlin, cutting off escape routes and encircling entire German formations.

The final Soviet offensives were marked by speed and ferocity, with soviet troops determined to crush any remaining resistance. The German army, unable to withstand the onslaught, was forced into a chaotic retreat, leaving behind countless dead and wounded. For many German soldiers, the prospect of falling into Soviet hands was terrifying, fueling desperate attempts to break out and surrender to the Western Allies instead. The Red Army’s relentless push not only sealed the fate of Berlin but also ensured that the Eastern Front would be remembered as the crucible in which Nazi Germany was finally destroyed.

Soviet troops advance into Berlin's urban suburbs.

The Impossible Choice: Fight or Surrender

Understanding why the Battle of Halbe happened at all requires grasping the impossible situation facing German soldiers and civilians in April 1945. For Wehrmacht personnel, surrender to the Soviets meant almost certain death or years in the gulag system. The statistics were stark: Germany lost 3 million soldiers during the war but lost an equivalent number–nearly 2 million more–in Soviet captivity between 1945 and 1954, when the last German prisoner was finally released.

For SS personnel, the choice was even starker – Soviet forces rarely took SS prisoners alive. For civilians, particularly women, surrender meant facing the systematic rape and brutalisation that had characterised the Red Army's advance through Eastern Europe. As one historian noted, "There are no civilians, there are no non-combatants really at this stage, particularly in the minds of the Soviets, as they're pushing ever so closer to Berlin."

This created a powerful motivation that transcended military discipline or Nazi ideology. General Busse motivated his troops not with promises of victory, but with hope: "Let's go west. Let's live. Let's get across the Elbe. Let's surrender to the Americans." The plan was to break through to Wenck's Twelfth Army and then continue west to American lines, where they expected more humane treatment.

The Soviets understood this psychology perfectly. Their propaganda leaflets dropped over German positions read: "All your hopes are destroyed." But for many Germans, any hope, however slim, was better than the certainty of Soviet captivity.

Information panel located at the Halbe War Graves

Artillery Rain and Tree-Burst Hell

The tactical reality of the Battle of Halbe was dominated by one factor above all others: Soviet artillery. Facing the German breakout were approximately 280,000 Soviet troops with 7,400 guns and mortars, 280 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 1,500 aircraft. Among these forces, the 1st Guards Breakthrough Artillery Division played a crucial role in smashing through German defences and using concentrated firepower to open gaps for Soviet advances. The Soviets had learnt to use the forest terrain to their advantage, deliberately timing their artillery shells to explode at tree-top height.

This technique, which had previously devastated American forces in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, created a deadly rain of wooden splinters that supplemented the metal fragments from the shells themselves. The sandy soil of the pine forests made digging foxholes impossible, leaving German troops with virtually no protection from this aerial bombardment.

Soviet aircraft relentlessly targeted German positions and supply lines, further isolating the encircled forces and hampering any organised resistance.

As one witness described it: “It’s the artillery which is bringing raining effectively death down from above. And there’s nothing you can do against artillery. It just comes. Doesn’t matter how skilled you are as a soldier… it just comes down to effectively dumb luck that it doesn’t hit you.”

The German forces found their armour largely useless in this environment. Tanks were vulnerable to destruction on the roads and struggled to gain proper traction on the sandy forest soil. The Soviets countered with dug-in Soviet tanks, establishing fortified positions that were difficult to dislodge and provided strong defensive fire against German breakout attempts. The dense forest terrain reduced visibility to mere metres, creating constant danger of ambush for both sides. Smoke from burning sections of forest, set alight by shell fire, provided some concealment from Soviet aerial reconnaissance but also disoriented German troops who lacked compasses and couldn’t see the sun for navigation. Both sides operated with few or no maps, which increased the chaos and confusion during the battle.

Destroyed vehicles along a forest track

The Civilian Tragedy Hidden in Plain Sight

Perhaps the most overlooked aspect of the Battle of Halbe is the civilian tragedy that unfolded alongside the military action. Thousands of non-combatants were caught in the battle zone, including local residents and refugees who had been fleeing westward for months.

In the town of Halbe itself, some civilians took pity on very young soldiers – the so-called “Kindersoldaten” or child soldiers – and allowed them to change out of their uniforms into civilian clothes. But the line between civilian and combatant had long since blurred. The Volkssturm, Germany’s civilian militia, had been pressed into service with basic weapons, and by this stage of the war, anyone capable of holding a Panzerfaust might be handed one and told to face a Soviet tank.

The civilian death toll remains unknown, but estimates suggest it could have reached 10,000. These deaths occurred not just from the fighting itself, but from the systematic targeting of civilian columns by the Soviet attack, as Soviet forces deliberately aimed their artillery and bombardments at specific targets, including groups of fleeing civilians. When American and Soviet forces linked up at the Elbe River, the famous footage of soldiers shaking hands over the bridge was actually staged. The real meeting point, just days earlier, was deemed unsuitable for filming because it was “peppered on the Soviet side of the river with all dead civilians that the Soviet artillery had been targeting”.

Spree forest track today

The Halbe Forest Cemetery: Memory Amid the Pines

Nestled among the tall, whispering pines, the Halbe Forest Cemetery stands as a solemn testament to the sacrifice and suffering of the Battle of Halbe. Here, in the heart of the forest where so many fell, thousands of German soldiers lie buried—many in mass graves, their identities lost to the chaos of war. Simple wooden crosses and understated markers bear silent witness to the final days of World War II, when the forests around Halbe became a killing ground for soldiers and civilians alike.

The cemetery, maintained by the German War Graves Commission, is more than just a burial site; it is a place of remembrance and reflection. Each year, families and visitors come to pay their respects, laying flowers and pausing in the quiet shade to honour those who never returned home. The Halbe Forest Cemetery is now the largest World War II cemetery in Germany, a stark reminder of the scale of loss suffered in the battle’s final, desperate days.

Amid the tranquillity of the pines, the cemetery serves as a powerful reminder of the devastating consequences of war. It stands not only as a memorial to the German soldiers who fought and died in the Battle of Halbe, but also as a call for peace and reconciliation—a place where the lessons of the past echo quietly through the forest, urging future generations never to forget the true cost of conflict.

Hale Forest Cemetery

Why Halbe Remains Forgotten

Despite its scale and significance, the Battle of Halbe remains largely unknown, even to many Germans living in the region. Several factors contribute to this historical amnesia, especially in the context of post-war Germany, where the memory of such battles has often been overshadowed or deliberately neglected.

First, Western audiences naturally focus on battles involving their own forces, such as those in Normandy, Market Garden, and the Rhine crossing, rather than the purely German-Soviet confrontations on the Eastern Front. The Eastern Front’s complexity, involving multiple nationalities and ideologies, makes it harder for Western audiences to understand and relate to.

Second, the battle gets lost in the broader narrative of the Battle of Berlin. When people think of Berlin’s fall, they focus on the city itself – Hitler’s bunker, the Reichstag, the famous Soviet flag photograph. But the Battle of Berlin actually began 90 kilometres outside the city, at places like the Seelow Heights and Halbe. The Seelow Heights alone involved 1 million men, including 768,000 infantry, four times larger than the entire Normandy operation.

Third, post-war sensitivities have kept the story buried. The Soviets didn’t want to discuss what many viewed as war crimes against civilians. The Germans, as the losing side, couldn’t bring attention to their own victimisation. And in modern Germany, there’s hypersensitivity to anything that might be seen as sympathizing with Nazi causes, even when discussing genuine human suffering.

Ultimately, the battle challenges comfortable narratives about the end of World War II. It reveals the savage reality of the Eastern Front, where both sides committed atrocities and the line between liberation and conquest became hopelessly blurred.

The line of advance for German soldiers into the town of Halbe today.

The Scale That Defies Comprehension

To understand why Halbe has been overlooked, it’s crucial to grasp the almost incomprehensible scale of Eastern Front operations. The Battle of Berlin involved over 3 million Soviet soldiers – a number that dwarfs most Western Front operations. These massive battles were coordinated by large army group formations, with German Army Group Centre and Army Group Vistula playing key roles in the final defensive efforts. The Seelow Heights, just one component of three Soviet fronts, was four times larger than the entire Normandy campaign, which landed 250,000 Allied troops. The scale and effectiveness of Soviet force dispositions during these operations were decisive in encircling and overwhelming German forces.

These numbers become even more staggering when considering Soviet record-keeping practices. The Soviets only officially recorded deaths of Communist Party members, leading to massive underreporting of casualties. Before the Battle of Berlin, party membership applications swelled as soldiers wanted their families notified if they were killed. Polish casualties – 80,000 Poles fought at the Seelow Heights – were never officially recorded at all.

The German War Graves Commission has recovered 1 million German war dead from Eastern Europe since 1945, recently completing a “Million for a Million” campaign to raise funds for repatriation. But there’s no equivalent Russian effort to recover Soviet remains, and Eastern European countries often bury their citizens who fought for Germany quickly and quietly, viewing their service as a source of shame.

Soviet artillery firing the opening barrage during the Battle for the Seelow Heights, April 1945

The Human Story Behind the Statistics

At its core, the Battle of Halbe reveals warfare as an inherently human story, not just a clash of machines and strategies. The soldiers on both sides had similar characteristics, similar hopes and fears. In any other circumstances, they might have been friends. But the cauldron of war, particularly the ideological war of the Eastern Front, brought out humanity’s ugliest side.

For the average German soldier at Halbe, part of the encircled army facing impossible odds, the motivation to keep fighting wasn’t ideological fanaticism but something more basic: “For the average man on the ground, it’s this sense of, well, I’m here now. I can’t do anything about my situation. I can’t run away, I can’t do anything about that. And then there’s a man next to me, who’s in the same boat that I am. So I gotta fight.”

This sense of duty to the soldier beside you, combined with the very real threat of execution by German military police for desertion, meant that for many, there simply was no choice. Roving court martials publicly executed soldiers and civilians for fleeing the battlefield, hanging them from street lamps with placards calling them cowards and traitors.

The Bundeswehr conducted a burial ceremony for bodies recovered after German unification.

Lessons from Hell's Cauldron

The Battle of Halbe offers several crucial insights into the nature of warfare and human behaviour under extreme stress. Author Eberhard Baumgart, who collected eyewitness accounts from the battle, identified key factors that determined who survived and who didn’t.

Success in the breakout depended largely on belonging to units where military authority and discipline remained intact: “To put it bluntly, the answer is those who belonged to regiments, battalions and companies where authority had remained intact and where there was a direct link between order and obedience. That’s where the combative spirit triumphed.” The discipline and organisation maintained by German units played a crucial role in preserving order and enabling coordinated attempts at breakout, even as chaos mounted.

The resolve displayed by German forces was rooted in their firsthand experience of Red Army cruelty: “The resolve displayed by the Ninth Army was also rooted in their firsthand experience of the Red Army’s cruelty. It was this certainty and the relentless barbarity shown in the ensuing slaughter which led to the scream ‘Run for your lives!’ reverberating through the ranks.” The Ninth Army's situation during the encirclement was especially dire, with their desperate actions and determination standing out as a testament to their resolve under extreme pressure.

But this desperation also led to the collapse of military effectiveness. Demoralised troops would retreat at the first obstacle, waiting for others to take casualties while hoping to tag along with successful breakthrough attempts. Those who did attempt the breakout faced continuous battles over 60 kilometres: “Those who embarked on the breakthrough ended up having to tackle one battle after another. The minute one obstruction had been surmounted, there was another one ahead of them, and then another. That happened day after day, for sixty long kilometres.”

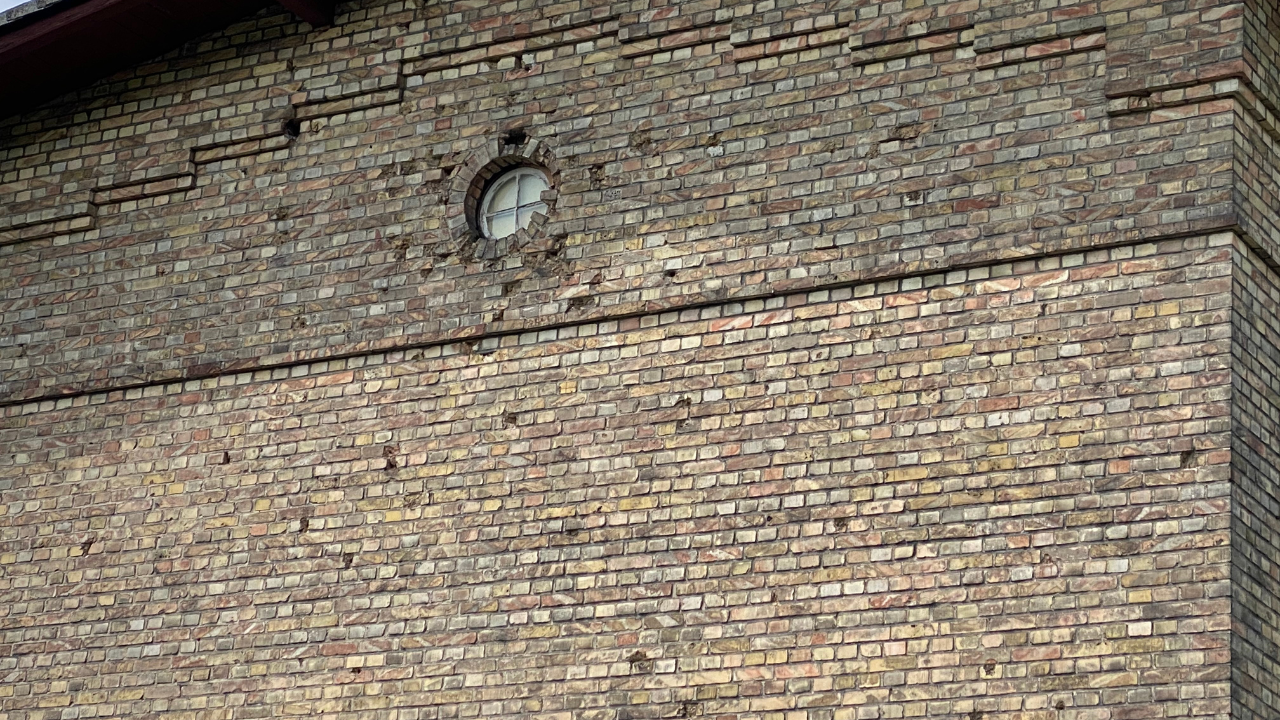

Battle scares still visible today on a residential property near the Halbe train station

The Aftermath: Success and Tragedy

Despite the horrific casualties, the Battle of Halbe achieved its primary objective for many participants. Approximately 30,000 German soldiers – just over one-third of those originally encircled – successfully reached the Twelfth Army’s lines. Combined with civilian refugees, these survivors then continued their westward retreat, eventually crossing the Elbe River at Tangermünde between May 4-7, 1945, to surrender to elements of the U.S. 102nd Infantry Division. In the final stages of the battle, Soviet forces plugged the last escape routes, sealing the fate of the encircled Germans and preventing further breakouts.

But the cost was enormous. The remaining 50,000 soldiers were killed or captured. The Red Army claimed to have taken tens of thousands of prisoners and reported significant victories in the destruction of German forces. Soviet casualties were also heavy, with thousands of Red Army soldiers buried at the Sowjetische Ehrenfriedhof cemetery near Baruth. The civilian toll may never be fully known, but it represents one of the war’s final tragedies – non-combatants caught between armies in the conflict’s dying days.

German POW’s April 1945

Conclusion: Remembering the Forgotten

The Battle of Halbe deserves to be remembered not as a footnote to the Battle of Berlin but as a crucial chapter in understanding the end of World War II and the human cost of ideological warfare. It reveals the desperate lengths people will go to when faced with impossible choices, the breakdown of military and social order in war’s final stages, and the blurred lines between combatant and civilian that characterised the Eastern Front and the brutal conflicts that swept across central Europe.

Today, as we approach the 80th anniversary of these events, the forests around Halbe remain a powerful memorial to those who died there. The silence that now pervades these woods stands in stark contrast to the hell that unfolded here in April 1945. Every year, more remains surface, reminding us that the full story of this battle – and the full accounting of its human cost – may never be complete.

The Battle of Halbe forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about warfare, ideology, and human nature. It challenges simple narratives of good versus evil, liberation versus conquest. Most importantly, it reminds us that behind every statistic, every casualty figure, every strategic decision, lie individual human stories of courage, desperation, and tragedy.

In remembering Halbe, we honour not just the soldiers who fought there but all those caught in war’s machinery – the civilians who had no choice but to flee, the young soldiers pressed into service, and the families torn apart by ideology and violence. Their stories deserve to be told, their sacrifices remembered, and their humanity acknowledged, even 80 years after the guns fell silent in the forests of Brandenburg.

This article was written by Matthew Menneke.

Matt is the founder and guide of 'On the Front Tours', offering military history tours in Berlin. Born in Melbourne, Australia, Matt's passion for history led him to serve in the Australian Army Reserve for eight years. With a degree in International Politics and a successful sales career, he discovered his love for guiding while working as a tour guide in Australia. Since moving to Berlin in 2015, Matt has combined his enthusiasm for history and guiding by creating immersive tours that bring the past to life for his guests.

The Tragedy of Halbe: A Forgotten Battle of WWII's Final Days and the Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Halbe, a tragic last stand in WWII's final days, saw German forces desperately attempt to surrender to the Allies rather than face Soviet retribution.

Destroyed vehicles in the Spreewald forest

Introduction: World War II

The Battle of Halbe, fought in the final days of April 1945, remains one of the most brutal and least-known clashes of World War II’s endgame on the Eastern Front. As Soviet forces tightened their noose around Berlin, the beleaguered German Ninth Army found itself trapped in a shrinking pocket near the small village of Halbe, 30 miles southeast of the Nazi capital of Nazi Germany. Faced with the prospect of Soviet captivity, the Ninth Army’s only hope was a desperate breakout attempt against all odds. The ensuing struggle would consume thousands of lives, both military and civilian, in a maelstrom of fire, steel, and close-quarters fighting. This is the tragic story of the Halbe Pocket.

Strategic Context: Soviet Advance

By mid-April 1945, the Red Army had the German capital, Berlin, firmly in its sights. As part of their final offensive to capture the city and end the war in Europe, Soviet commanders sought to isolate and destroy the German Ninth Army. Positioned east of Berlin and defending the Oder River line, the Ninth Army, commanded by General Theodor Busse, represented a significant threat to the Soviet advance.

The Soviet Army, with its 2.5 million strong force, played a pivotal role in this final offensive, relentlessly pushing towards Berlin.

To eliminate this obstacle, Stalin ordered his two most formidable front commanders, Marshal Georgy Zhukov of the 1st Belorussian Front and Marshal Ivan Konev of the 1st Ukrainian Front, to encircle the Ninth Army and sever their lines of retreat. Zhukov would attack from the east, while Konev closed in from the south. Their ultimate objective was to trap the Germans in a pocket and prevent them from reinforcing Berlin’s defenses. This maneuver was part of a broader strategy to break through Army Group Centre and tighten the siege on Berlin.

Marshal Georgy Zhukov and Marshal Ivan Konev respectively

For General Busse and his men, estimated at around 200,000 soldiers along with thousands of refugees fleeing the Soviet advance, the prospect of being captured was unthinkable. The Soviets’ reputation for brutality towards prisoners, fueled by years of bitter fighting and Nazi atrocities on Soviet soil, meant that surrender was not an option. The Ninth Army’s only hope was to attempt to break out of the impending encirclement to the west and reach the relative safety of General Walther Wenck’s Twelfth Army.

However, any breakout attempt would have to punch through multiple layers of Soviet forces in the dense, swampy terrain of the Spreewald forest. This labyrinthine region of marshes, rivers, and thick woods presented a daunting challenge for mechanized warfare. The Germans would have to navigate narrow, easily congested roads and bridges, all while under constant Soviet fire. The stage was set for a desperate battle of attrition.

The Pocket Forms:

Under intense pressure from Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front from the east and Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front from the south, the Ninth Army’s defensive lines, manned by German forces, began to crumble. Soviet armour and infantry, backed by a formidable array of artillery and air support, tore through German positions along the Oder and Neisse Rivers. Despite determined resistance, Busse’s divisions could not hold back the Red Army tide.

Hitler and Busse at the last front-line meeting at the CI Army Corps, Harnekop Castle, March 3, 1945

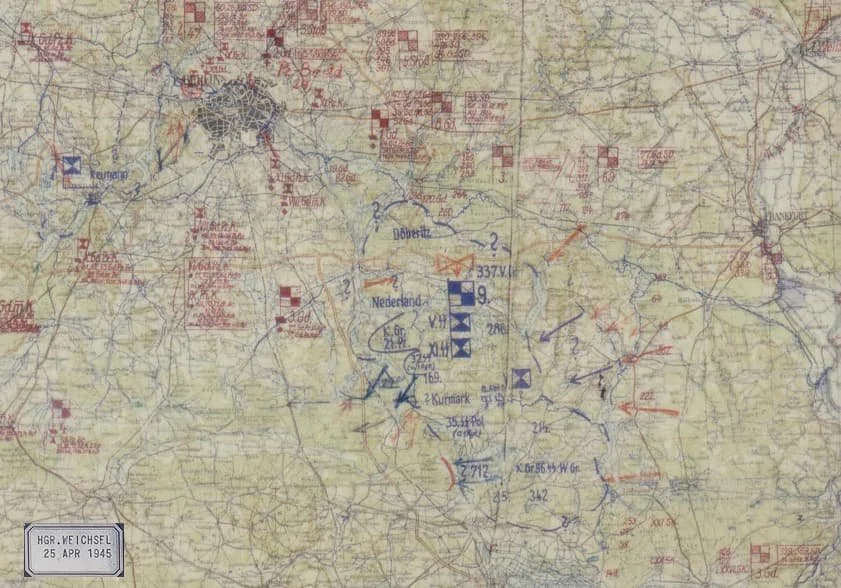

By April 25th, Soviet pincers had closed around the Ninth Army, trapping them in a pocket roughly 15 miles wide and 8 miles deep in the Spreewald south of the village of Halbe. The Soviet 3rd and 28th Armies formed the northern edge of the pocket, while the 3rd Guards Tank Army and 13th Army sealed off the south. The Germans were now cut off from outside help and faced the daunting prospect of a fighting retreat through the Spreewald.

Soviet soldiers hoisted flags and banners to mark their victory, leaving graffiti as a testament to the liberation of the Reichstag.

Inside the “Halbe pocket,” conditions quickly deteriorated into a living nightmare. Cut off from resupply, the Germans soon began to run perilously low on food, ammunition, and medical supplies. Columns of vehicles, both military and civilian, jammed the narrow forest roads, presenting prime targets for marauding Soviet aircraft. Artillery fire rained down incessantly, shattering the woods and turning the roads into killing zones littered with burned-out wrecks and corpses of men and horses.

Map of the formation of the 9th Army pocket

As the pocket shrank under constant Soviet pressure, soldiers and refugees were forced into an ever tighter space, enduring intense privation and a mounting sense of claustrophobic doom. Makeshift field hospitals overflowed with wounded while the dead lay unburied. Food and water grew scarce. The hellish conditions eroded morale and unit cohesion, with some soldiers resorting to looting and abandoning their posts. The once-formidable Ninth Army was disintegrating.

Choosing Surrender: German Fears and Preferences in the War's Final Days

As the war in Europe drew to a close, German forces increasingly sought to surrender to the Western Allies rather than the Soviet Union. Several factors drove this preference. Firstly, there was a profound ideological enmity between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The Nazis viewed the Soviets as racially inferior and their communist ideology as a mortal threat to the German way of life.

Surrendering to the Soviets was thus seen as a deeply humiliating betrayal of core Nazi beliefs. Secondly, the Germans feared the prospect of brutal Soviet reprisals. They were acutely aware of the atrocities committed by Soviet forces as they advanced through Eastern Europe and anticipated harsh treatment and retribution as prisoners.

The Germans' own guilt compounded this fear; they had waged a pitiless war of annihilation against the USSR, seeking to destroy it as a political entity, murder and enslave its Slavic population, and colonize its territory. With the Soviets having suffered over 20 million deaths at German hands, the desire for vengeance was palpable. In contrast, the Germans had much less animosity towards the Western Allies, whom they had primarily fought to secure their rear before turning on the USSR.

Surrendering to the Americans or British was thus seen as a far preferable fate. This dynamic played out vividly in the Battle of Halbe, where desperate German forces fought to break out to the west and surrender to the Americans rather than fall into Soviet hands.

Halbe: The Eye of the Needle and Soviet Forces

Realizing that the pocket could not hold out for long, General Busse ordered his troops to mass west of Halbe to prepare for a breakout towards the spearheads of General Wenck’s Twelfth Army, which was advancing from the west. The small riverside village of Halbe, strategically located at a crossroads in the heart of the Spreewald, would be the focal point of the escape attempt. Troops soon began calling it “the eye of the needle” through which the entire Ninth Army would have to pass. The Army Group Vistula, under immense pressure, played a crucial role in the defensive preparations and strategies during this period.

Destroyed German vehicles

Starting on April 28th, the breakout began in earnest, spearheaded by the SS Panzer Division “Kurmark” and elements of the 502nd SS Heavy Tank Battalion. The Germans threw their remaining armour and veteran infantry units into the thrust, hoping to punch a corridor through the Soviet lines. However, the narrow confines of the forest roads and the density of Red Army soldiers meant that the battle rapidly devolved into a chaotic, brutal slugfest at close quarters.

Savage fighting erupted at strong points like the Halbe cemetery and railway embankment. At the cemetery, the struggle reached a crescendo of horror, with German troops using the stacked corpses of their own dead as makeshift breastworks against Soviet attacks. The armoured vehicles of both sides duelled at point-blank range amidst the tombstones while infantry grappled in hand-to-hand combat among the crypts.

Soviet war map showing the battle lines of the 9th Army encirclement.

Nearby, the elevated railway embankment became a scene of equal carnage. Soviet troops entrenched along its length poured fire into the advancing Germans, turning the railbed into a charnel house. Burned-out tanks and shattered bodies choked the narrow confines. The fighting devolved into a series of ruthless small-unit actions, with squads and platoons clashing in a maelstrom of bullets, grenades, and flamethrowers.

As the battle raged, thousands of terrified refugees found themselves caught in the crossfire. Desperate columns of civilians, their meagre possessions piled on carts and wagons, clogged the roads. Many were killed by stray shells or machine-gun fire as they tried to flee westward. Others fell victim to vengeful Soviet troops, who viewed them as complicit in German crimes. The fate of the refugees added an especially tragic dimension to the unfolding disaster.

Breakout and Aftermath of German Forces

After days of brutal fighting that gutted the Ninth Army, a group of about 25,000 haggard German troops finally managed to break through the Soviet gauntlet and reach the temporary safety of Wenck’s lines. The survivors emerged from the Spreewald battered, bloodied, and traumatized by their ordeal. Many had lost everything—their units, their comrades, their families. The physical and psychological scars would linger long after the guns fell silent.

The Soviet Union commemorated the battle by honouring the Hero of the Soviet Union recipients and awarding medals to Soviet personnel for their actions during the Battle of Berlin.

Twisted metal still visible from the aftermath of the Halbe Pocket breakout attempt.

But the Germans’ escape had come at a staggering cost. In their wake, they left scenes of unimaginable devastation and carnage. Corpses carpeted the forest floor, piled in grotesque tangles where they had fallen. Burned-out hulks of tanks, trucks, and wagons littered the roadsides for miles, a testament to the ferocity of the fighting. The pungent stench of death hung over the battleground.

The human toll of the Halbe pocket was appalling. Scholars estimate that at least 40,000 German soldiers perished in the breakout attempt, with another 20,000 wounded. Between 20,000 and 30,000 hapless refugees were also killed, cut down in the crossfire or deliberately targeted by Soviet troops. The Red Army claimed to have taken 60,000 prisoners, many of whom would endure years of forced labour in Soviet gulags.

The Battle of Halbe, while small in scale compared to the titanic clashes of the Eastern Front’s earlier years, nonetheless epitomized the relentless brutality and human tragedy of the war’s endgame. It laid bare the utter collapse of the once-vaunted Wehrmacht, ground down by years of attrition and material disadvantage. It highlighted the pitiless calculus of total war, in which entire armies and civilian populations could be sacrificed in the pursuit of victory. And it underscored the Third Reich’s dismal moral bankruptcy, as Nazi leaders consigned thousands to senseless death in a battle already lost.

Halbe also represented a microcosm of the “total war” that had engulfed the Eastern Front, erasing distinctions between soldiers and civilians. Alongside the doomed German military units fought the Volkssturm, a ragtag people’s militia of old men and teenagers pressed into service in the regime’s final days. Refugees fleeing the Soviets found themselves thrust onto the front lines, where they perished alongside the troops meant to protect them. In the Spreewald inferno, all became targets.

German POWs

The fall of Berlin, marked by Adolf Hitler's death by suicide in the bunker beneath the Old Chancellery building, signalled the end of the Third Reich. The subsequent Battle of Berlin led to the city's fall to Soviet forces, resulting in significant casualties and the razing of the city. The Soviet War Memorial at Tiergarten commemorates this pivotal event and serves as a pilgrimage site for Red Army veterans and their families.

Remembering Halbe:

Despite the intensity of the fighting and the scale of the tragedy, the Battle of Halbe has long remained a historical footnote, overshadowed by the high-profile fall of Berlin unfolding simultaneously just 30 miles to the north. The chaotic nature of the final days on the Eastern Front, combined with the thorough Soviet conquest of eastern Germany, meant that many records of the battle were lost or deliberately suppressed.

For decades after the war, East Germany’s communist authorities actively discouraged research into the Halbe pocket and other desperate battles fought on what became their territory. The story of Halbe complicated the triumphalist postwar Soviet narrative, which emphasized the Red Army’s heroic liberation of Germany from Nazism. Acknowledging the scope of civilian suffering and the brutal realities of the Spreewald fighting did not align with the official historiography.

German Army soldiers bury remains in Halbe cemetery, 2013

The Soviet War Memorial in Tiergarten, Berlin, constructed using materials from destroyed Nazi office buildings, serves as a significant reminder of the Red Army's role and the sacrifices made, including the surrounding cemetery for fallen Red Army soldiers and the annual VE-Day commemorations.

As a result, the Battle of Halbe faded into relative obscurity, mourned by veterans and families of the fallen but little known to the broader public. Only after German reunification in 1990 did historians begin to document and chronicle the battle extensively. Halbe has since become a subject of intensive research and sombre commemoration.

Today, the memory of Halbe is preserved by a melancholy war cemetery in the nearby forest, where over 22,000 German soldiers and civilians are interred in mass graves. A small museum in the village also endeavours to tell the story of the doomed breakout attempt. In recent years, several powerful and harrowing books have brought the battle’s history to a wider audience, including Tony Le Tissier’s “Slaughter at Halbe” and Anne-Katrin Müller’s “The Battle of Halbe: The Destruction of the Ninth Army.”

Halbe War Grave Cemetery

Beyond its memorials and chroniclers, however, Halbe endures as a sobering reminder of the human suffering unleashed by war at its most unsparing. On this small, blood-soaked battlefield, where shell-shocked conscripts fought alongside hardened veterans, where terrified families fleeing an implacable foe fell beside the fanatical remnants of the Waffen-SS, we glimpse the Eastern Front distilled to its brutal essence. It is a harrowing picture of depravity, desperation, and ordinary people caught in the meat grinder of total war. The broader context of the war's end also saw German troops seeking to surrender to the Western Allies, fearing the fate of Soviet captivity, and the Western Allies' subsequent withdrawal to agreed-upon boundaries after Germany's unconditional surrender.

Conclusion:

The Battle of Halbe, while a small chapter in the vast saga of World War II, nonetheless looms large in the bloody drama that played out in central Europe during the spring of 1945. It offers a microcosmic glimpse into the agonizing final days on the Eastern Front, with all their attendant chaos, horror, and moral ambiguity. It reveals the human face of the German army's collapse—from the travails of General Busse's doomed divisions to the plight of the terrified refugees swept up in their wake.

Halbe deserves to be remembered not only as a testament to the immense suffering and sacrifice of those caught in its maelstrom but also as a cautionary tale about the profound costs of war fought to the bitter end. In an age when "total war" became an all-consuming reality, erasing distinctions between soldier and civilian, front line and home front, Halbe reminds us of the price paid by all—the vanquished no less than the victors—when nations clash without restraint or mercy.

As we reflect on this tragic battle 75 years later, let us honour the memory of those who struggled, suffered, and perished in the Spreewald cauldron. Germans and Soviets, men and women, young and old—all were consumed in the inferno unleashed by a brutal, rapacious war and the totalitarian ideologies that fueled it. May their sacrifice not be forgotten, and may it stand as a sombre warning to future generations of the horrors lurking in the heart of total war.

The article was written by Matthew Menneke.

Matt is the founder and guide of 'On the Front Tours', offering military history tours in Berlin. Born in Melbourne, Australia, Matt's passion for history led him to serve in the Australian Army Reserve for eight years. With a degree in International Politics and a successful sales career, he discovered his love for guiding while working as a tour guide in Australia. Since moving to Berlin in 2015, Matt has combined his enthusiasm for history and guiding by creating immersive tours that bring the past to life for his guests.

The Battle of Berlin: The Final Blow to Hitler's Third Reich

The Battle of Berlin in 1945 was the final major offensive in Europe, marking the end of World War II.

Introduction:

In the spring of 1945, as the Second World War in Europe drew to a close, the once-mighty German Reich lay in ruins. The Soviet Red Army, having turned the tide of the war in the East, stood poised on the banks of the Oder River, ready to strike the final blow against Nazi Germany. Their target: Berlin, the capital and heart of Hitler's crumbling empire. The Battle of Berlin, which raged from April 16 to May 2, 1945, would be the last major offensive in Europe and the death knell for the Third Reich.

The battle was a culmination of years of bitter fighting between Germany and the Soviet Union, a titanic clash of ideologies and armies that had left millions dead and reshaped the map of Europe. For Stalin and the Soviet leadership, the capture of Berlin was not just a military objective but a matter of national pride and vengeance for the immense suffering inflicted on their country by Hitler's invasion. For the Germans, the defence of their capital was a desperate last stand, a fight to the finish in which surrender was not an option.

Soviet tanks advance through Berlin

Battle of Berlin - Battlefield Tour

The Importance of Berlin:

Berlin in 1945 was not just the administrative capital of Germany but the symbolic heart of the Nazi regime. It was here that Adolf Hitler rose to power in the early 1930s, consolidating his grip on the nation and transforming Germany into a totalitarian state. The city was a showcase for the grandiose vision of the Third Reich, with wide boulevards, massive government buildings, and imposing monuments designed to project an image of strength, power, and permanence. Berlin was the nerve centre of the Nazi war machine, home to the regime's top leaders and decision-makers.

But Berlin was more than just a political capital - it was also a crucial industrial and transportation hub. The city's factories churned out a steady stream of weapons, vehicles, and other supplies to feed the voracious appetite of the German military. Berlin's extensive rail network and its position at the crossroads of Europe made it a vital link in the supply chain that sustained the Nazi war effort on multiple fronts.

As the Red Army approached Berlin in April 1945, the city took on an even greater significance. For the Soviets, capturing Berlin would be the ultimate prize, a way to avenge the staggering toll of 26 million Soviet citizens killed in the war and to assert their dominance in postwar Europe. Stalin was determined to take the city before his Western allies, advancing from the other direction. The Soviet leader knew that whoever controlled Berlin would have a major say in the future of Germany and the continent as a whole.

For Hitler and the Nazi leadership, the fall of Berlin would mean the end of their "Thousand Year Reich." The Führer had ordered the city to be defended to the last man, vowing never to leave the capital alive. He and his top lieutenants retreated to a bunker deep beneath the Reich Chancellery, directing the city's defences and clinging to increasingly unrealistic hopes of a last-minute reprieve. Hitler's propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, called on Berliners to fight to the death, warning that the Soviets would unleash a wave of destruction and atrocities if they took the city.

The Bleak Situation for the German Army:

The frontlines in late April 1945

As the Soviet forces prepared for their final offensive, the situation for the German Army was dire. The Wehrmacht, once the pride of the Third Reich, was a shadow of its former self. Years of continuous warfare had depleted its ranks, and the relentless Allied bombing campaigns had shattered its industrial base, making it increasingly difficult to replace lost equipment and personnel.

German soldiers dug in along the Oder river

The German High Command was acutely aware of the desperate situation. Resources were scarce; the troops were often young, inexperienced, or elderly men hastily conscripted from the Volkssturm, a national militia. The once-feared Panzer divisions were now few in number, and many tanks were old or in disrepair. Fuel shortages meant that even those that were operational could not be effectively deployed.

Despite these challenges, the German Army prepared to defend Berlin with a grim determination. General Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, organized the city's defences, knowing full well that there would be no reinforcements. The strategy was to turn Berlin into a fortress, with barricades, anti-tank obstacles, and fortified positions throughout the city. Civilians, including women and children, were pressed into service to dig trenches and build defences.

The German soldiers, many of whom were aware that they were fighting a losing battle, were motivated by a combination of fear, loyalty, and the knowledge that surrender to the Soviets could mean death or harsh captivity. Propaganda played a role as well, with Nazi officials exhorting the troops to fight to the last man to protect their homeland from the perceived barbarism of the advancing Red Army.

The German Army, under-equipped and outnumbered, faced the overwhelming might of the Soviet juggernaut. The stage was set for a brutal, no-quarter struggle that would reduce much of central Berlin to rubble. The battle for Berlin would not only determine the fate of the city but would also seal the fate of the Third Reich.

Seelow Heights Battlefield Tour

The Soviet Offensive:

The Soviet assault on Berlin codenamed "Operation Berlin," was a monumental military undertaking that involved some 2.5 million soldiers from the 1st Belorussian Front under the command of the renowned Marshal Georgy Zhukov and the 1st Ukrainian Front led by the equally formidable Marshal Ivan Konev. This massive force was supported by an awe-inspiring array of military hardware, including 6,250 tanks, 7,500 aircraft, and a staggering 41,600 artillery pieces. It was, by any measure, one of the largest and most complex military operations ever undertaken in the history of warfare.

Soviet artillery firing on German positions, 3 am April 16 1945

The offensive began on April 16 with a massive, earth-shaking bombardment of the German defences along the Oder-Neisse line. The sky lit up with the flash of thousands of guns, and the ground trembled under the weight of the explosive barrage. Zhukov's forces, the hammer of the Soviet offensive, attacked from the centre and north, while Konev's men, the anvil, hit the German lines from the south. Despite fierce and determined resistance from the outnumbered and outgunned Germans, who fought with the desperation of men who knew they were the last line of defence for their capital, the Soviets managed to break through. Slowly, inexorably, they pushed the defenders back towards the outskirts of Berlin.

Marshal Ivan Konev

“It is we who shall take Berlin, and we will take it before the Allies.” - Six Meetings that Changed the 20th Century (2007)

Marshal Georgy Zhukov

“The longer the battle lasts the more force we'll have to use!” - A History of the Modern Age (1971)

In these opening days, one of the most critical and brutal battles was the fight for the Seelow Heights, a heavily fortified area east of Berlin that represented the last major obstacle before the city itself. Here, the Germans had constructed three formidable defensive lines bristling with trenches, anti-tank ditches, and extensive minefields. The battle raged for four long, bloody days, with the Soviets suffering heavy casualties as they threw themselves against the German defences. German guns cut down wave after wave of Soviet infantry and armour. However, still, they came on, driven by a combination of courage, desperation, and the implacable will of their commanders. Finally, on April 19, after a titanic struggle that left the ground littered with the dead and dying, the Soviets overran the last German positions on the heights, and the road to Berlin lay open.

The Battle for the City:

As the Soviet troops entered the outskirts of Berlin, they faced determined, even fanatical resistance from a hodgepodge of Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS units, Hitler Youth, and Volkssturm militia. The city had been turned into a fortress, with streets barricaded, buildings fortified, and critical intersections turned into strong points bristling with machine guns, anti-tank weapons, and panzerfaust-wielding defenders. The Soviets had to fight for every block and building in brutal, close-quarters combat, clearing out cellars and attics with grenades and flamethrowers and engaging in hand-to-hand fighting in the rubble-strewn streets.

One of the most iconic and symbolic moments of the battle came on April 30, when Soviet troops stormed the Reichstag, the historic parliament building that had been the seat of German power. The fighting was fierce and unrelenting, with the Soviets having to clear the building room by room, floor by floor, in a deadly game of cat and mouse with the die-hard German defenders. Snipers, machine guns, and booby traps took a heavy toll on the attackers, but they pressed on with grim determination. Finally, as the sun began to set on the evening of May 1, a group of Soviet soldiers managed to fight their way to the roof of the shattered building and raise the Soviet flag over the Reichstag, a red banner fluttering in the smoke-filled air. It was a moment of immense symbolic significance, signalling to the world that the heart of Nazi Germany had fallen and that the end of the war in Europe was at hand.

Soviet T-34 engaged in battle along a Berlin street

Staged Soviet photograph showing a sniper position

Meanwhile, in his dank, claustrophobic bunker deep beneath the Reich Chancellery, Adolf Hitler, the once all-powerful Führer of the Third Reich, lived out his final, desperate days. As the Soviet troops drew ever closer, the sounds of battle echoing through the concrete walls, Hitler, his mind and body ravaged by disease and despair, prepared for the end. In a hastily arranged ceremony, he married his longtime mistress Eva Braun, and then, on April 30, as Soviet soldiers fought their way into the Chancellery garden above, Hitler and Braun committed suicide, the Führer shooting himself in the head while his bride took poison. Their bodies were hastily cremated in a makeshift pyre in the Chancellery garden, a grim and ignominious end to the man who had once dreamed of conquering the world and establishing a thousand-year Reich.

Hitler’s Berlin - the rise and fall

Aftermath and Legacy:

The Battle of Berlin, which raged from April 16 to May 2, 1945, ended with the unconditional surrender of the city's remaining defenders. The once-proud capital of the Third Reich lay in ruins, its streets littered with debris and the bodies of the fallen. The human cost of this final, decisive battle had been staggering: over 80,000 Soviet soldiers were killed, and more than 250,000 were wounded in the fierce fighting. German losses, both military and civilian, numbered in the tens of thousands. The civilian population of Berlin also suffered terribly, with countless thousands killed in the crossfire or by suicide as the Red Army closed in.

Soviet soldiers celebrate the fall of Berlin

White flags flow from windows - symbolising total surrender

The fall of Berlin marked the effective end of the Third Reich. With Hitler dead by his own hand in his underground bunker and the country occupied by Allied forces, the German High Command had no choice but to agree to unconditional surrender. The final capitulation came on May 8, 1945, bringing an end to the war in Europe and the nightmare of Nazi tyranny that had plagued the continent for six long years.

The battle also had far-reaching political consequences that would shape history for decades to come. The Soviet capture of Berlin, ahead of their Western allies, gave Stalin a significant bargaining chip in the following postwar negotiations. The division of Germany and Berlin into Soviet and Western zones of occupation set the stage for the Cold War, which would dominate global politics for the next four decades. The Iron Curtain that divided Europe into communist and capitalist spheres was born in the ruins of Berlin.

Today, the Battle of Berlin stands as a warning to the immense destructive power of modern warfare and the depths of human suffering it can cause. The scale of the fighting, the devastation wrought on the city, and the sheer loss of life on all sides serve as a grim reminder of the horrors of war. At the same time, the battle also serves as a tribute to the courage and sacrifice of those who fought to end the tyranny of Nazi Germany and bring peace back to Europe. The soldiers of the Red Army, who bore the brunt of the fighting and suffered the heaviest losses, showed incredible bravery and determination in the face of fierce resistance from a fanatical enemy.

Allied victory parade July 1945

The scars of the battle can still be seen in the streets and buildings of Berlin, a city that has risen from the ashes to become a symbol of resilience and renewal. The bullet holes and shrapnel marks on the facades of old buildings, the memorials to the fallen, and the museums dedicated to the history of the war all serve as reminders of the city's painful past. But Berlin has also become a vibrant, multicultural metropolis, a hub of art, culture, and innovation that looks to the future with hope and optimism.

In the end, the legacy of the Battle of Berlin is a complex one, marked by both tragedy and triumph. It represents the end of one of the darkest chapters in human history but also the beginning of a new era of peace, democracy, and international cooperation. As we reflect on the events of those fateful days in April and May 1945, we must remember the sacrifices made by those who fought and dedicate ourselves to the cause of building a world free from the scourge of war.

Conclusion:

Clearing the ravished streets of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin was the final cataclysmic act in the European theatre of World War II. It pitted the full might of the Soviet war machine against the fanatical but crumbling defences of the Third Reich in a struggle for the very heart of Germany. The battle left the city in ruins and cost tens of thousands of lives, but it also brought an end to the Nazi regime and its dreams of conquest and racial supremacy. Today, as we mark the 75th anniversary of this historic event, we remember the courage and sacrifice of those who fought and died in the battle, and we renew our commitment to building a world of peace and understanding.

The article was written by Matthew Menneke.

Matt is the founder and guide of 'On the Front Tours', offering military history tours in Berlin. Born in Melbourne, Australia, Matt's passion for history led him to serve in the Australian Army Reserve for eight years. With a degree in International Politics and a successful sales career, he discovered his love for guiding while working as a tour guide in Australia. Since moving to Berlin in 2015, Matt has combined his enthusiasm for history and guiding by creating immersive tours that bring the past to life for his guests.